AUGUST 2024. By Nicola Gale, RPh (APA), MPH.

More about Nicola Gale.

Nicola Gale is a clinical pharmacist with an out-patient liver clinic in Calgary, Alberta that provides low-barrier care for Hepatitis C Virus (HCV) infections for people with experiences of criminalization, unstable housing, and substance use. She also recently completed a Masters in Public Health and works remotely with the BC Centre for Disease Control supporting with monitoring and evaluation for the Test, Link, Call (TLC) project.

I attended a conference last year where a presenter described accessing Hepatitis C Virus (HCV) care, as “simple but not easy”. This is a phrase that I’ve often returned to when thinking about my experiences working in healthcare as a clinical pharmacist, and as a researcher with Test, Link, Call (TLC), a program that provides free cellphones and peer support to people to help them to access care for HCV, HIV, and syphilis. As a healthcare provider that really grew into this work over the COVID-19 pandemic, I feel that “simple but not easy” exemplifies the challenges, and opportunities, that we have to improve and rethink access to testing and treatment for sexually transmitted and blood-borne infections (STBBIs) in BC and Alberta.

On one hand, incredible medical and pharmaceutical advances have provided us with technologies and treatments that make it easier than ever to get tested and treated for STBBIs. This includes the discovery of a class of medications called the Direct Acting Antivirals (DAAs) that can cure over 95% of all chronic HCV infections with minimal side effects and in as little as 8-12 weeks. I count myself lucky to be a part of a generation of providers that get to tell people that we can cure a previously incurable chronic infection(!). Not only that, accessing cure can prevent long-term complications associated with untreated HCV infections including scarring of the liver (also known as fibrosis), cirrhosis (severe scarring), liver cancer, and even an increased risk of death.

Digital Connectivity as a Social Determinant of Health

On the other hand, making sure that those technologies and treatments make their way into the hands of everyone who needs them is a challenge. This has been particularly true during the COVID-19 pandemic, in which we experienced significant disruptions to STBBI testing and service delivery. We’ve also seen shifts in social and structural determinants of health that impacted rates of STBBIs and access to care, including increases in opioid-toxicity deaths, rising costs of living and housing, and a primary care crisis that has left many people unattached to a family doctor. In particular, the pandemic sped up the shift from in-person to remote healthcare delivery, which has helped to improve access for some, but has also left many others behind. As digital technology has become an integral tool for accessing healthcare, individuals without access to a cellphone are at a disadvantage when searching for health information, participating in telehealth, and following up with their healthcare providers. As a result, this divide in digital health equity has been recognized as a ”super social determinant of health” that intersects with all other social determinants.

The populations that are at the highest risk of acquiring HCV (people with experiences of criminalization, unstable housing, and people who use drugs) are less likely to have access to a cellphone and are also less likely to access care. We see this reflected in provincial data: in 2019 in British Columbia, 52,641 new cases of HCV were reported, with 80% of those occurring in people who use drugs (PWUD). When compared between people who use drugs and those who don’t, we can see that there is a large gap in access between people who get access to HCV treatment (and cure) and those who don’t, with 73% of people without a history of intravenous drug use (IVDU) accessing and starting curative HCV treatment, compared to only 52% of people who have a history of IVDU. In the 2022 BC Harm Reduction Client Survey (HRCS), among the 503 PWUD who participated, 58% reported not having a cell phone, or not having minutes or a plan on their device if they did own one.

Addressing Gaps with the TLC Project

To close this access gap, the Test, Link, Call (TLC) project was developed to help improve STBBI testing, treatment, and cure for people who use drugs, people experiencing unstable housing, and people with experiences of criminalization and incarceration. TLC incorporates a unique service delivery model that provides participants with a free cellphone, a 6-month unlimited talk and text phone plan, and support from a Peer Health Mentor (a person with lived experience) for system navigation and help connecting with a clinic. As a collaborative quality improvement project, TLC helps to bridge service access gaps as clients move between community providers, correctional facilities, acute care, housing, and primary care.

Since its launch in October 2021, TLC has enrolled 273 participants for access to HCV care and 26 for access to HIV care. TLC is successfully connecting with groups that have been deemed the “hardest to reach” populations: over 60% of all enrolled TLC participants are experiencing homelessness or unstable housing, over 50% are involved in addiction care, and 30% were active IV drug users at the time of enrollment. Among the 245 TLC participants with a confirmed chronic HCV infection, 139 (57%) were started on curative treatment. For participants involved with TLC for over 1 year, the treatment start rate increased to 68%, which highlights the importance of long-term support in overcoming barriers to HCV care.

Incorporating Social Prescribing to Improve Service Delivery

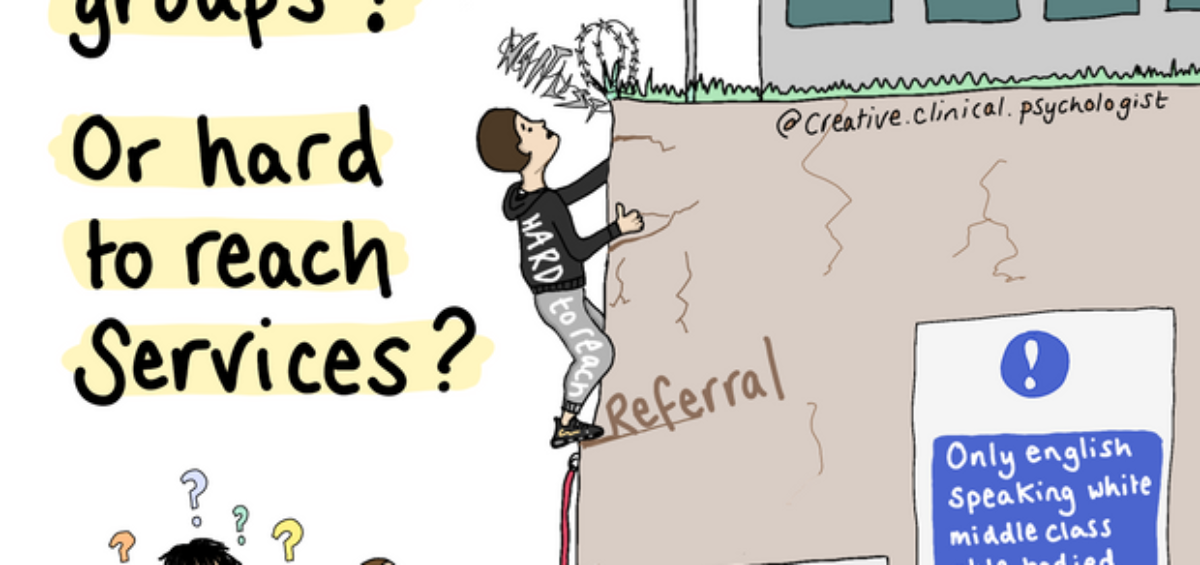

https://www.patreon.com/posts/hard-to-reach-71983167

Working in frontline care myself, being involved in a project like TLC gives me hope that it’s possible for our systems to be reoriented towards addressing the needs of the community. This requires a crucial shift away from wondering why we can’t find the “hard to reach clients” and instead refocusing instead on how to make our “hard to reach services” better. Collaborations like these allow the medical community to benefit from the expertise of people with lived experience, and highlights how health and social care can be treated as not just separate spheres, but as one and the same. Incorporation of “social prescribing” allows us to address social determinants of health like digital exclusion, access to nature, or social connectivity, alongside medical care. While this may be “simple, but not easy” to achieve, we can find inspiration in the progress of innovative programs like TLC that are helping to build equitable systems that ensures everyone has the opportunity to access the benefits of a cure.

As originally seen on the Pacific Public Health Foundation’s blog posts.